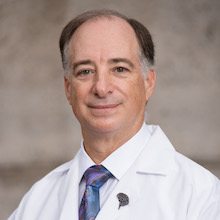

Dr. Michael Sisti will tell you it was his destiny, to not only be a neurosurgeon, but to be one here at the Neurological Institute. ”It was a combination of family and geography,” He says. That, a chain smoking scout leader and a bunch of laboratory cats.

“My family is very traditional Italian,” says Sisti. “Very smart, and my father’s side of the family is very educated. My grandfather Sisti went to Fordham and studied pharmacy.

In fact, my initial interest in medicine came from books that he had.” He refers to a 4000 page, 8 volume set of The Encyclopedia of Health.

”My grandfather’s name was Michael Sisti. I am named after him. I was young but I have very clear memories of going through those books with him.” When he died, his grandmother gave him the books and they are in his home today.

Sisti’s Dad and Uncle were engineers. He says, “They were people who knew how to do anything—to fix anything, whether it was working on the Throgsneck Bridge or the atomic bomb.”

On his mother’s side, his grandfather was a master carpenter. “He built the house we lived in by hand,” says Sisti. “His tool kits were like our surgical trays. Not only was he an amazing carpenter he would make it beautiful and he would make it fun.”

The influence of all these engineers and craftsmen naturally lead Sisti toward an engineering degree in college. He says, “Cooper Union was legendary in my background. I knew from both my father and my uncle’s work that engineers could do anything; business, law, research, or medicine.”

His degree from Cooper Union has given Sisti a unique perspective in medicine.

From the beginning, he has approached it from a technical point of view and as a craftsman.

An early mentor of his, Neurosurgeon, Dr. Edgar Housepian says, “His engineering background has helped him in his career. He has embraced technology and is one of our best young surgeons. He put stereotactic radiosurgery on the map. The work he has developed with the Gamma Knife was one of his major contributions which I have followed with admiration.”

Dr. Housepian was and still is at the Neurological Institute in New York but he met Sisti in Tenafly, New Jersey when Sisti was just 8 years old. He was in Cub Scouts with his son David.

“David was a really good friend of mine,” says Sisti, “His mom Marion was our den mother. I knew his dad was a brain surgeon and to me, the whole idea was just mind-bending.”

“He was a wonderful kid,” says Housepian. “He was very bright and he was really animated in everything he did. Now that he is older,” he laughs, ”he has calmed down a little. He’s a very good, thoughtful, and compassionate doctor. He has a great bedside manner and his patients love him.”

Sisti was also good friends with the son of a Columbia neurologist living in Tenafly, Dr. Robert Lovelace.

“His son Robert and I were in Boy Scouts together. Troop 86,” says Sisti. “Becoming an Eagle Scout, was one of the most arduous things I did in the 60s.”

The leader of their troop was a man named Louis Bishoff and he had a dream; he wanted to walk the entire Appalachian Trail from Maine to Georgia—all 2200 miles.

Sisti says, “Every summer we would take a trip, and by the way, Louis Bishoff was not a healthy guy. He was a chain smoker. He had terrible lungs. It was an agony for this guy to make those trips. He did the whole damn thing though. He walked from Maine to Georgia with adolescents. It took him like 15 years but he did it and I did 800 miles with this guy. I’m talking in the 60s,” says Sisti. “This is when nobody was back-packing.”

Sisti remembers one trip in particular, “I’m 14 years old and we are going to walk 70 miles of the Great Smokey’s National Park.”

After walking up this giant mountain the first day out, Sisti broke his arm. “We walked back down to the main road and hitchhiked to the nearest doctor,” says Sisti. “No X Ray, no nothing, he just grabbed it, I screamed like hell, he set it and slapped a cast on and said I was good to go. Then I had to walk back up the mountain. I did the ten day trip with my arm in a cast and a pack on my back.”

Sisti describes the experience as one of those ten-year-plus goals that has a lot of steps along the way—just like becoming a neurosurgeon.

“You want to become a neurosurgeon?” he asks. “Your gonna have to walk from Maine to Georgia and you know what? Along the way, your going to break your arm and you better just slap a cast on and muddle through it, because that is what its like.”

At that time, Sisti didn’t know he would be a neurosurgeon but he was becoming more interested in medicine. He says, “Breaking my arm was my first real experience with the medical field and what I learned was—it works!”

In high school Sisti worked part time and summers at Englewood Clinical Laboratories. There, he learned how to run lab tests including a highly complicated one called High Pressure Liquid Chromatography.

At that time, his friend’s dad, Dr. Lovelace was doing research at the Neurological Institute and needed someone who could perform that very test. So, he offered Sisti a job.

“I didn’t have a drivers license,” says Sisti, “and Dr. Lovelace said he’d drive me. So, at the age of 17, I was being chauffeur driven by a professor of neurology to and from work at the Neurological Institute—you see, my future was already mapped out.”

By the end of high school, Sisti was seriously contemplating a career in medicine. Cooper Union didn’t offer the necessary pre-med courses so he turned to Columbia University.

There, he took a course called Animal Structure and Function with Dr. Walter ‘Wally’ Bock. The course came with a cat dissection lab.

Sisti remembers, “Wally Bock taught biology as an engineering discipline. He would discuss the structure of a bone like a structural element. His whole approach through biology and evolution was through the lens of an engineer.

I said, my God, this is the link. This is how biology, evolution and engineering make living things work. Once I took that course I knew I was going to be a doctor. That was seminal for me. Oh, and by the way, guess where Dr. Bock lives–Tenafly, New Jersey.”

Sisti said that, while he struggled through his engineering classes, this class came naturally. “In the end,” says Sisti, “Dr. Bock offered me a job, even though I was not a Columbia student, to TA his cat dissection lab.”

Sisti continued to work in that lab during his first years of medical school at Columbia, where he then moved on to TA the human anatomy lab. “Bock was a great teacher. That is what I learned most from him—how to teach,” says Sisti.

Sisti carried those lessons forward into the operating room at Columbia. First, as a senior resident teaching junior residents, and now as a senior faculty member. “Over the years,” he laughs, “I can’t tell you how many lives those cats have saved.”

After completing his residency, he was one of the few residents offered a job in the Department of Neurosurgery here, under their new Director, Dr. Ben Stein.

After completing his residency, he was one of the few residents offered a job in the Department of Neurosurgery here, under their new Director, Dr. Ben Stein.

Since retired, Dr. Stein handpicked nearly all of the neurosurgeons working in the Department today. He says, “I loved all of the guys but the one that I felt closest to was Mike Sisti. I felt like he was a son. Mike was one of the clearest thinkers. He’s just a delightful guy to be around. He’s got a lot of ideas.”

Dr. Stein says, “When I got a little long of tooth, I would have him [Sisti] scrub in with me; some of those operations went 8 hours. So I could go out and relax and know that he was doing the job (probably better than me) and we could spell each other.”

Stein is also responsible for the unique sub-specialization of each member of the Department. He knew that dedicating their talents to one specific area of neurosurgery would create exceptional skill.

Today, Sisti specializes in intercranial tumors. Dr. Housepian says, “Sisti is probably our expert on microsurgery of acoustic tumors; tumors that come off one of the nerves that goes into the internal auditory canal. It is delicate work and he does it very well. I send patients to him often and they are all very satisfied. He is very good to them.”

Sisti has now been at the Department of Neurosurgery for 33 years. “Except for one year at the NIH to do research,” he says. “But if you really want to roll back the clock, I started here when I was 17 in 1972 in Dr. Lovelace’s lab.

I work with the best people in the world. I have a job that I love—that I am good at. I get to help people with incredibly complex problems and make a major difference in their lives. I am where I am supposed to be.

I work with the best people in the world. I have a job that I love—that I am good at. I get to help people with incredibly complex problems and make a major difference in their lives. I am where I am supposed to be.

It was my destiny,“ Sisti laughs. “I never had a chance.”